Where Did the Stars Go? How Light Pollution Took the Night

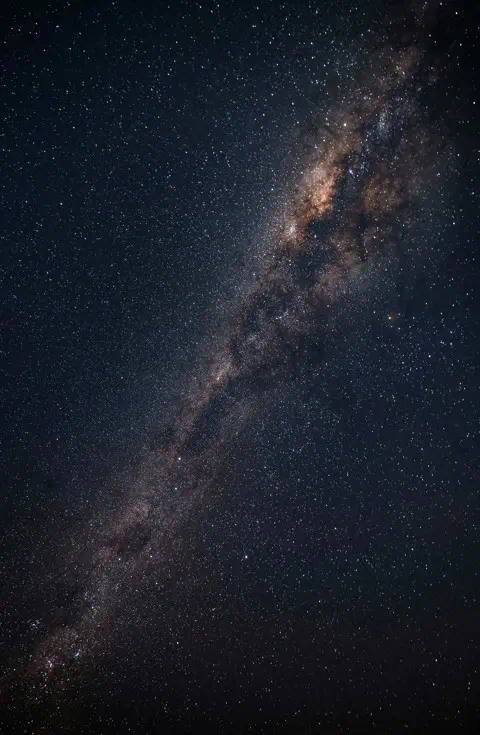

There’s something quietly devastating about looking up at the night sky and seeing... nothing. Just a gray haze where there should be galaxies.

If you're like most people living in a city or suburb, you probably haven’t seen the Milky Way in years. Maybe ever. You might spot Venus, a planet or two, a few stubborn stars, but the night sky most of us grew up drawing as kids? That’s gone.

The Problem Isn’t the Stars. It’s Us.

Light pollution is the excessive or misdirected use of artificial light that brightens the night sky which results in washing out stars and also the disruption of some ecosystems. It comes from sources like streetlights, buildings, signage, and even vehicle headlights (looking at you, high-beam LED headlights that feel more like interrogation lights than road safety).

Light pollution is one of those things that crept up on us. But when you think about it, you can see why. It's not loud, It doesn't stink or have a smell. It doesn’t clog your lungs or gives the water that weird metallic taste (you don't quite notice the taste until you taste natural clean water...). But even though light pollution lacks all of these factors, it has completely altered the way humans experience nighttime. And it happened fast.

According to a 2023 study published in Science, the night sky is getting brighter by about 9.6% each year globally and 10.4% in North America. This data comes from more than 50,000 observations collected between 2011 and 2022 through the citizen science project Globe at Night. If the trend continues, skyglow could double roughly every eight years. To put this into perspective: a child born today in a moderately dark area, who could see 250 stars, might only see 100 of them by the time they reach adulthood. A generation is literally erasing the night sky with fewer than half the stars their parents saw, even if they live in the same place.

According to a 2016 study published in Science Advances titled "The New World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness," over 80% of the world's population, and 99% of people living in the U.S. and Europe, now live under skies polluted by artificial light. The Milky Way is no longer visible to about 60% of Americans who live in urban areas. Some of us, didn't even know there was a time where you could see the Milky Way with your naked eye (seriously, not until working on this article did I know that not too long ago, people were able to see the Milky Way without the use of a telescope!) These findings highlighting just how widespread light pollution has become.

But This Isn’t Just About Feelings, Right?

Actually… yes, it kind of is. The stars are one of the few truly universal human experiences. For tens of thousands of years, people all over the world looked up at the same night sky and told stories, marked seasons, and thought about other worlds. Just imagine lying down on a dark field and staring at a dark sky full of white luminous dots...You'll have to just imagine because that sky is not a common sight anymore. With light pollution comes a loss of wonder and that almost spiritual connection to the cosmos. A whole dimension of our environment, erased by careless overlighting and endless sprawl.

But beyond that, light pollution has tangible and real impacts. It disrupts wildlife migration and reproduction, especially for nocturnal species. One of the most poignant examples is the decline of fireflies, whose delicate bioluminescence depends on dark surroundings to attract mates. As artificial lighting floods more of their natural habitats, firefly populations are dropping, with some species facing the risk of extinction. Fireflies rely on bioluminescent signals to find mates, a process that depends on naturally dark surroundings. When artificial light invades their habitats it can overwhelm or mask their flashes. This makes it harder for fireflies to locate each other and reproduce, leading to population declines. In essence, the brighter our nights become, the more invisible fireflies become to each other. Sea turtles, too, are affected. Hatchlings rely on the moonlight reflecting off the ocean to find their way to the water, but coastal lighting often lures them inland instead, where survival is unlikely. These disruptions ripple through ecosystems.

Wait, but there's more.

Light pollution doesn't just affect wild animals and insects...it also affects us...physically, by interfering with our sleep patterns. See, exposure to artificial light at night disrupts our circadian rhythm (the internal biological clock that manages our sleep and wake cycles). Blue-rich white lights, like those emitted by many LED streetlamps and screens, can suppress melatonin production, which makes it harder to fall and stay asleep. This disruption isn't just about feeling tired...it's much worse. Studies have linked excessive nighttime light exposure to increased risks of insomnia, depression, obesity, and even certain cancers.

That's scary.

In a world where sleep is already hard to come by, the glow of urban lighting silently chips away at our health and wellbeing.

Aside from our life span, light pollution has a significant impact to something else that has a very real impact to us...money.

Light pollution wastes energy, about 30% of outdoor lighting in the U.S. is wasted, according to the International Dark-Sky Association. This inefficiency costs approximately $3.3 billion annually and results in around 21 million tons of CO₂ emissions each year. This is roughly about 4.5 million cars' output each year. These figures highlight how inefficient lighting is not just an aesthetic or ecological problem, but an economic and environmental one too. This happens when lights are left on all night without timers or motion sensors, when fixtures send light into the sky instead of focusing it downward, and when areas like parking lots, signage, and building facades are excessively illuminated well beyond what’s necessary for safety or functionality. In essence, we’re paying to light up a space that doesn't need it (the sky).

All of these impacts are interconnected, but they’re not inevitable. The way we light our world is shaped by choices such as where we build, how we regulate, and what we prioritize which brings us squarely into the domain of planning.

How Planning Plays a Role

Light pollution is a land use issue, a design issue, a regulation issue, and therefore a planning issue.

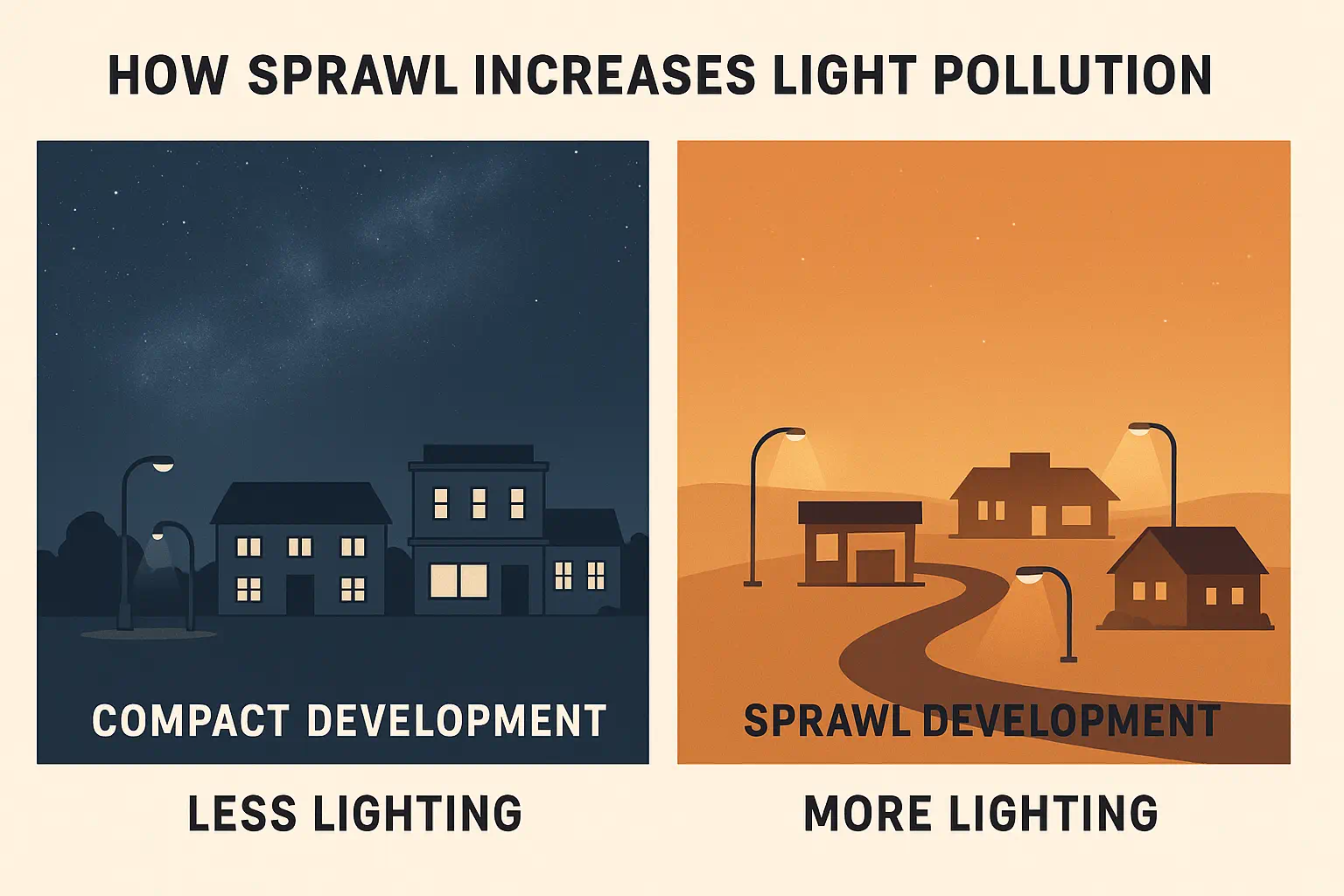

Zoning and Sprawl:

Low-density development means more land covered by lighting. Think about it, with low density development you need more highways and roads to illuminate. You have fewer places where darkness is preserved with every cul-de-sac, frontage road, and standalone big-box development bringing its own constellation of streetlights and parking lot lights. Unlike compact urban forms where lighting can be shared and concentrated, sprawling areas require duplicated infrastructure, that is, each new development must build its own roads, streetlights, signage, and parking lots, rather than connecting to a centralized system. This repetition spreads artificial lighting over much larger areas and increases the total number of fixtures contributing to skyglow. But this pattern doesn't just add more lights, it also pushes them into places that were once dark, like rural outskirts or natural buffer zones. As subdivisions and commercial corridors creep outward, they displace habitats and encroach on dark sky areas, compounding both ecological and astronomical impacts.

Lighting Codes (or Lack Thereof):

Many cities either don’t have outdoor lighting standards, or the ones they have are outdated and inconsistently enforced. In the absence of comprehensive ordinances, businesses and property owners often default to excessive or poorly designed lighting that are driven by aesthetics or the perceived need of security, or even the need for advertising visibility. Without policy guidance on things like proper shielding, light fixtures are free to emit in all directions like a runaway disco ball. Some older lighting codes predate modern LED technology entirely, leaving a regulatory gap as newer, brighter fixtures are installed without updated standards. But even in cities with ordinances on the books, enforcement can be difficult due to limited staffing or lack of awareness, especially in older neighborhoods or unincorporated areas where oversight is minimal. As a result, light quality and placement often go unchecked, leading to inconsistent and inefficient lighting landscapes.

Parking Minimums and Commercial Corridors:

Big-box stores, strip malls, and even medium-scale developments often over-light their parking lots, which can end up looking like airport tarmacs at night...and nobody likes that. These spaces are often bathed in high-intensity, unshielded lighting that creates excessive glare and contributes significantly to skyglow. In most cases, these lighting decisions are driven by liability fears, marketing visibility, or simple inertia, not safety data. According to the International Dark-Sky Association and the American Medical Association, overly bright lighting does not necessarily improve safety and may actually reduce visibility by creating sharp contrasts and shadows. Excessive lighting can create glare, especially from unshielded fixtures, making it harder for drivers and pedestrians to see clearly at night. The AMA has specifically warned that high-intensity LED lighting can negatively affect nighttime visibility and public health. Furthermore, these lights are often left on overnight, long after business hours, illuminating empty lots for no real purpose except habit or perceived expectation. The result is an enormous amount of wasted energy, disrupted ecosystems, and further erosion of natural nighttime darkness. Outdoor lighting in the U.S. consumes around 120 terawatt-hours of energy each year, enough to power New York City for two years...have you seen how large New York city is!?!? And 30–35% of that lighting is completely wasted! This ends up costing roughly $3.3 billion and creating about 21 million tons of CO₂ emissions annually. This design is an avoidable environmental cost with a massive footprint.

Street Design:

Cobra-head lights and high-pressure sodium bulbs were once the standard for street and outdoor lighting. These older systems were far from efficient, but they produced a softer, amber-colored glow that had relatively less impact on the night sky. Now, many cities are switching to LED lighting for its energy efficiency and lower long-term maintenance costs. However, if not carefully selected and calibrated, LEDs can exacerbate light pollution. "Whiter" LEDs emit more short-wavelength blue light, which scatters more in the atmosphere. This leads to heightened skyglow and causes the night sky to appear washed out and starless. Additionally, the sharp intensity of poorly shielded or overly bright LEDs can create visibility problems for both pedestrians and drivers, while undermining dark-sky preservation efforts. The key lies not just in using LEDs, but in using the right kind which are typically those under 3000 Kelvin, and ensuring fixtures are properly shielded and directed downward.

There Are Solutions and Planning Can Help

The good news? Light pollution is one of the rare environmental problems we can actually undo. It's literally flipping a switch, and BOOM the stars come back...ok, maybe is not that easy but it is one of the rare planetary problems we can actually *undo...if we want to.

Here’s what planners can do:

- Update lighting ordinances to require fully shielded fixtures that direct light downward. This reduces skyglow and glare by preventing light from spilling upward or sideways where it isn’t needed.

- Limit the intensity and color temperature of outdoor lighting, especially LEDs. Lower color temperatures (3,000 Kelvin or less) reduce blue light emissions, which scatter more and contribute significantly to skyglow.

- Designate dark-sky zones near natural areas, parks, and rural buffers. These special areas use stricter lighting rules to protect nightscapes for both wildlife and people.

- Promote smart growth and compact development patterns that reduce the total area requiring illumination. Dense, walkable communities share infrastructure and lighting more efficiently than sprawling developments.

- Encourage motion sensors and timers for lighting in commercial and institutional buildings. These controls ensure that lights are only used when needed, saving energy and reducing unnecessary light pollution.

- Educate developers and homeowners on responsible lighting, including the environmental and aesthetic benefits. Public awareness can lead to voluntary changes and broader adoption of best practices for lighting regulations.

Flagstaff: A Case Study in Dark Sky Leadership

Cities like Flagstaff, AZ and Sedona have become leaders in this space. Flagstaff, in fact, was the first International Dark Sky City and has strict regulations on lighting, with measurable results. The city began its journey as early as 1958 with the banning of commercial searchlights, and in 1989 it adopted zoning caps on outdoor lighting based on lumens per acre. By the time it was designated an International Dark Sky City in 2001, Flagstaff had already set a global precedent. Satellite and ground-based measurements reveal that the light dome over Flagstaff is about 14 times dimmer than that of Cheyenne, Wyoming, a similarly sized city without comparable protections. These results are due in part to the city's use of low-pressure sodium lights and dark-sky compliant amber LEDs. Monitoring has shown that despite continued population growth and development, Flagstaff has managed to maintain relatively stable sky brightness levels, around Bortle Class 4–5, which refers to moderately dark skies where the Milky Way is visible but faint and skyglow is still present, typically seen in rural or rural-suburban transition areas. On the Bortle Scale (ranging from Class 1 for pristine dark skies to Class 9 for heavily light-polluted inner cities), this level represents a significant preservation of night sky quality. The city also uses tiered lighting zones and strict audit protocols to ensure compliance, showing that well-enforced regulations can successfully preserve the night sky even in growing urban areas.

We Don't Just Build Cities. We Build Experiences.

It's important to remember that planning doesn’t just shape streets and zoning maps. When we push for policies and designs in our built environment, we are pushing to create spaces for people.This includes how people experience time, space, and the wonder of the world above us. The sky used to feel infinite. Now it feels like it ends at the nearest LED billboard.

But it doesn’t have to.

If we’re willing to rethink how we light our streets, our signs, our homes and businesses, we can start to undo some of the damage. The stars are still up there...waiting. We just need to give them a chance to shine again. And maybe, just maybe, we’ll remember what it felt like to stand outside as a kid, tilt our heads back, and feel small in the best possible way.

Light pollution may b estealing our stars, but there's something else that is having a negative impact on our lives. Check out how cars are destroying America

%20(1200%20x%20237%20px)%20(300%20x%2059%20px).webp)