Walk into your bedroom.

A bed. A dresser. Maybe a window that lets in some light. Feels personal, right?

Now imagine that same space, maybe even larger, dedicated to your car.

Just a slab of asphalt, painted lines, maybe a bit of oil stain.

It sounds ridiculous. But it’s real. The average U.S. parking space takes up more square footage than the average bedroom.

And that tiny fact says a lot about the way we design our cities, our homes, and our priorities.

How big are we talking?

Let’s do some math.

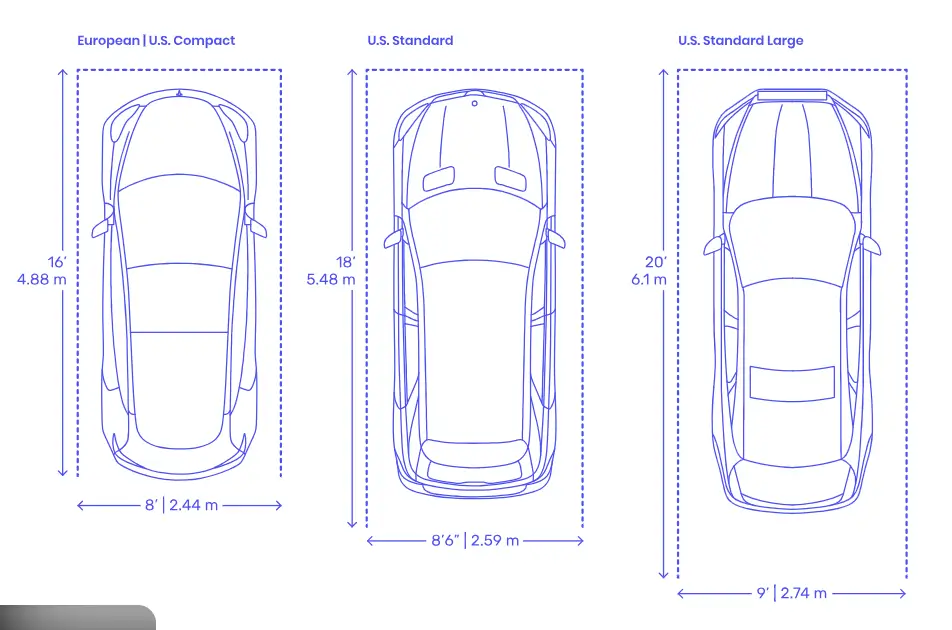

A standard parking stall in the U.S. is about 9 feet wide by 18 feet long. That’s 162 square feet, and that’s the bare minimum. Once you include drive aisles, turning space, landscaping buffers, and access zones, the true footprint jumps closer to 300–330 square feet per car.

Compare that to a typical bedroom, especially in older homes or apartments, at 120–140 square feet.

Meaning: for every spot you give your car, you could fit a person comfortably sleeping, studying, or raising a kid.

Sightline Institute once summed it up perfectly: “Your car’s bedroom is bigger than yours.”

And when you multiply that across a city, it starts to look less like an exaggeration and more like a quiet tragedy of planning.

Where all this space goes

We’ve normalized it. We expect it.

Every store, restaurant, apartment complex, and church must have its rows of paved, striped rectangles.

They’re not free. Each one costs somewhere between $5,000 (surface) and $25,000–$50,000 (structured) to build. Underground? Double that.

Developers pay it upfront. Residents pay it monthly, baked into rent or home prices. Everyone pays through higher costs, bigger footprints, and fewer walkable places.

But because we’ve been doing it for 70 years, we stopped seeing it.

We don’t look at parking lots and think, “That could’ve been housing.”

We think, “Where am I supposed to park?”

How we got here

After World War II, car ownership exploded. The planning profession, well-intentioned at the time, decided to keep cities from “clogging up.”

Zoning codes began to require minimum parking standards:

- One or two spaces per housing unit

- Several per thousand square feet of commercial space

- Even mandates for churches, bowling alleys, or laundromats

These numbers weren’t based on hard science. They were guesses, often copied from a 1950s planning manual and duplicated across the country.

So our codes guaranteed that every new building would serve cars first and people second.

And now? We’ve paved so much of America that parking lots collectively cover more land than some entire states.

What this means for housing

Imagine if every apartment had to build an extra 300 sq. ft. of space, not for people, but for cars.

That’s what parking minimums do.

A developer building 10 apartments might need to dedicate space for 20 stalls. That’s roughly 6,000 square feet, the equivalent of five or six more units.

Even when underground, those stalls cost tens of thousands of dollars each, which means fewer affordable units and higher rents.

That’s why many planners and housing advocates are pushing cities to remove or reduce parking minimums.

When Buffalo repealed its minimums in 2017, the result wasn’t chaos, it was creativity. Developers started using land for new housing, small businesses, even public plazas. Cities like Minneapolis, Portland, and Gainesville followed. The results: more flexibility, more projects, more homes.

A psychological twist

This isn’t just about geometry. It’s about mindset.

We’ve built cities that tell us cars deserve more comfort than we do.

They get their own driveways, garages, curbs, and laws protecting their space.

People? We get “No Loitering” signs.

We worry about finding a parking space more than we worry about finding affordable housing.

We build neighborhoods where walking to the store feels impossible, but storing a two-ton vehicle feels essential.

It’s wild when you stop and think about it: we treat car comfort as a right, and human comfort as a luxury.

Environmental cost

Beyond money and land, parking carries heavy environmental weight.

All that pavement creates urban heat islands, temperatures in parking-heavy zones can be 10°F hotter than surrounding areas.

It also worsens stormwater runoff, floods local drainage systems, and eats into green space that could support trees or reduce flooding.

And because every parking space encourages driving, it reinforces the cycle of emissions, congestion, and sprawl.

In short, we don’t just overbuild parking, we build cities around it.

The cultural shift happening now

Change is coming.

Dozens of U.S. cities are repealing minimums. Developers are experimenting with “unbundled parking”, where tenants choose whether to pay for a space or not. Some are converting old parking lots into infill housing or green space.

And new policies are treating parking as a tool, not a mandate.

- Oregon banned minimums near transit in 2023.

- California’s AB 2097 does the same for areas within half a mile of transit stops.

- Planners in states like Florida and Tennessee are testing “shared parking” models that reduce over-supply.

Bit by bit, we’re beginning to reimagine the city, not as a machine for cars, but a home for people.

A planner’s reflection

The next time you open a site plan and see a neat grid of rectangles labeled “PARKING,” pause.

Visualize each one as a small bedroom.

Now multiply it by 100.

That’s an entire apartment building worth of human space.

An entire block of opportunity, gone before it’s even built.

And when someone asks, “Why does housing cost so much?” or “Why do cities feel so empty?” you’ll know part of the answer.

Because somewhere along the line, we decided the car deserved a bigger room than we did.

%20(1200%20x%20237%20px)%20(300%20x%2059%20px).webp)